An Understanding of Math Anxiety: How Emotional Realities Affect Student Learning

Math anxiety is a subconscious, maladaptive strategy students use to ensure their psychological safety in a stressful or unproductive learning environment. To the student, math anxiety is an innate barrier to success, stemming from internalized beliefs of their inability to succeed. It is a symptom of broader experiences that have negatively impacted their sense of self and their ability to engage in productive learning. We as educators must be intentional about understanding math anxiety from an emotional perspective so that we approach struggling students with greater compassion, and in doing so, help alleviate the effects of math anxiety.

Math anxiety is real, and it’s much more than feeling nervous or worried around math. Growing up, I never really struggled with math, but my twin brother always did. I remember him spending hours at the table every night trying to learn things he couldn’t seem to understand, confused about why he “just didn’t get it”, being told he was failing because he needed to pay attention and work harder. I can remember what he looked like, sitting there hunched over for hours, pencil barely moving, fingers roughly twirling in his hair. I can remember his frustration and the whispers that maybe he struggled because he just wasn’t that smart. I can even remember people comparing us, and his tears when he was held back for not passing the state math test. Every day of school brought more opportunities for him to feel like a fool and a failure.

During a given school day, students who struggle with math anxiety have to live with the constant reminders that math is intimidating, overwhelming, and impossible to grasp. The realities of this struggle can be excruciating. I worked with a colleague who shared with me her experiences of math anxiety. For her, math was the only subject she struggled with . . . which is why she was repeatedly shamed for being lazy and stupid since only a lazy, stupid person would struggle for “no reason”. No one could understand that her struggle was involuntary. My colleague became so inundated with fear and shame, that the very thought of doing math made her physically ill and weepy. These feelings persisted throughout her collegiate experience.

The things I have described are unfortunately all too common for those who struggle with math anxiety. In 2022 Krzysztof Cipora and his team of researchers completed a research synthesis exploring largely undisputed claims about math anxiety. Cipora and his team noted many things, namely that math anxiety is distinct from other forms of anxiety, independent from learning difficulties/developmental challenges, that it starts in early elementary and increases until adulthood, and that it can be alleviated (Cipora et. al., 2022, pp.10-11) 1.

These things are important to note because struggling with math anxiety is not a fixed state. There are circumstances that induce math anxiety and circumstances that reduce math anxiety. There are practices that weaken mathematical understanding and practices that strengthen mathematical understanding. There are strategies that aggravate maladaptive coping and strategies that alleviate the need for maladaptive coping. However, none of this can be effectively practiced until math anxiety is better understood.

To this end, we must understand that math anxiety is a maladaptive coping mechanism developed in response to the stressful, emotional realities struggling with math anxiety can bring. Understanding this can help educators more compassionately and effectively work with their students to overcome math anxiety and achieve greater learning outcomes. However, before we can explore these strategies and practices, we must first understand that math anxiety is not the advent of poor pedagogy; but rather, a response to the circumstances that led to the anxiety.

In this article I’ll be presenting a broader, evidence-based exploration of certain psychological understandings and principles. A broader focus is necessary as there is no way to accurately or effectively encapsulate the myriad factors, nuances, and interactions between the external and internal realities that every human holds. In our time together, I hope to share with you an understanding of the emotional realities of math anxiety. These realities will be explored through an overview of the causes, characteristics, and common outcomes of math anxiety as well as ways that we, as educators, can more compassionately and proactively account for math anxiety in our classrooms.

How Anxiety Develops

In order to better understand math anxiety, we must first understand how anxiety is formed. There is a difference between the normal feeling of anxiety and the anxiety that disorders one’s behavior. The Cleveland Clinic notes that an anxiety disorder is characterized by “[experiencing] a lot of stress over a long period [of time]” (Cleveland Clinic, 2020)2. There are many everyday situations that can make someone feel anxious like trying to remember the name of the person in front of them or missing an exit on the interstate. These moments of situational anxiety can make someone feel worried or dread, but these feelings are momentary and do not outlast the situation that provoked them. It is when these feelings become pervasive and persist outside of their catalyzing context that an anxiety disorder begins to form. While there is stigma around the term disorder, it is nothing more than a clinical designation for a disruptive state of being. There is no moral defect or existential failing that causes mental disorders, let alone anxiety. The World Health Organization defines a mental disorder as “a clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotional regulation, or behavior” (WHO, 2022)3. They note that these disorders are “usually associated with distress or impairment in important areas of functioning” and that anxiety disorders result “from a complex interaction of social, psychological and biological factors” (WHO, 2023)4. This anxiety can be general or experienced in specific situations. It can result in individuals avoiding the people, situations, or activities that make them feel anxious. The World Health Organization goes on to note that individuals who struggle with anxiety disorders may experience many symptoms including, but not limited to: trouble concentrating or making decisions, nausea or abdominal distress, trouble sleeping, and having a sense of impending danger, panic or doom (WHO, 2024)5. In 2022, the Anxiety & Depression Association of America reported that “over 40 million adults (19.1% of the population) [in the United States] have an anxiety disorder” with “specific phobias [affecting] 19.3 million adults or 9.1% of the U.S. population” (ADAA, 2022)6. Though the causes of anxiety are incredibly nuanced, there is one consistent, contributing factor: stress. Stress is the body’s way of communicating with the brain in order to discern real or potential threats, respond accordingly, and protect the self from harm.

The role of stress and the stress response is explored in a 2018 review article, written by a team of researchers at the University of São Paulo, titled, “A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications”7. This review article explores the research history and neurobiological functions of stress and the stress response. Stress is a complex neurobiological process wherein external stimuli trigger diverse internal processes in the brain and body. Both physical and psychological stressors can trigger the stress response. Each type of stressor triggers a different pathway of brain and body responses as physical stressors threaten to overwhelm the biological systems needed for survival (like in cases of severe blunt force trauma or blood loss) while psychological stressors are anticipated threats to one’s current state, whether those threats are physical or psychological. Physical stress responses trigger physical systems and are automatic while psychological stress responses involve some cognition in addition to physical responses. The stress responses to physical stressors work more immediately and promote things like alertness. The stress responses to psychological stressors are slower by comparison but trigger stress responses that are longer-lasting (like the release of glucose for additional energy).

In this way the brain and body work together, coordinating a complex response to stress that involves the activation of different aspects of the nervous system and bodily organs. These activations release different hormones that kick start physical responses designed to quickly deal with stress and allow the body to return to homeostasis. When the stress response is functioning normally, it lasts no longer than a few days. When an individual struggles with anxiety, the stress response can last for much longer. When the stress response exists longer than the activating stressors, an individual is kept in an ongoing stress response.

The Relationship between Anxiety, Needs, and Safety

This prolonged stress response prevents an individual from feeling safe and hinders them from meeting their physical and psychological needs. Merriam-Webster defines needs as the “physiological or psychological [requirements] for the well-being of an organism”8. Having needs is inherent to the human condition. Satisfied needs are integral to a high quality of life, something every human strives to have. A high quality of life is a subjective condition wherein an individual experiences high levels of "health, comfort, and happiness"9. The exact circumstances that create high levels of satisfaction in these areas change with the individual. Still, there are commonalities in the needs that each human strives to meet. This interpretation of needs is well-explored in Abraham Maslow’s “A Theory of Human Motivation”10.

In his theory Maslow notes that humans tend to organize their behavior around getting their needs satisfied (Maslow, 1943, p. 370), before going on to examine needs categorized into the following stages (read bottom-to-top):

The bottom tiers, physiological needs and the need for safety and security, make up the basic needs. The higher tiers make up the psychological needs. Maslow explains that any desire for “higher”, more psychological needs cannot emerge until the more basic, physiological needs are met (Maslow, 1943, p. 370). In this dynamic theory, the attention paid to each tier is determined by ever-changing interactions between environment and well-being. Every need is given attention by the individual, yet needs at a lower tier are naturally prioritized as they are more needed for immediate survival. Maslow goes on to note that when these more basic needs go unmet, they begin to dominate the individual, gearing their “receptors and effectors, intelligence, memory, and habits” towards satisfying that need (p. 374). To illustrate this, Maslow gives an example of a person enduring hunger (p. 374-5). I will briefly explain his example and then use it to expound upon the interplays between stress and safety behaviors.

In his example, Maslow notes that satisfying their hunger becomes the starving individual’s sole driver. Their mind, body, and behavior are geared towards meeting that physiological need. In this state, only the capacities that would satisfy their hunger are prioritized and used. The starving individual cannot meaningfully engage with anything other than what will find them food as any other focus would ultimately jeopardize survival. Needs for safety, love and belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization still exist, yet circumstances force them to lie dormant and unsatisfied. So, even though each level of the hierarchy is necessary, no other needs can be thought of, let alone pursued and satisfied, until that hunger is satiated. In these conditions, the individual is locked into a constant survival state wherein their highest end is to sate their physical hunger. It is in this way that an unsatisfied need displaces everything but what is required to meet that need. This is inherently dysfunctional, and while the severities of this displacement are most obvious when physiological needs are unmet, a similar impact is felt when an individual’s needs for safety and security go unmet. When an individual is able to meet their physiological needs, the next needs to be prioritized are the safety needs. Safety is deeply tied to this article’s understanding of math anxiety because math anxiety is but one maladaptive way the mind organizes itself to meet an individual’s needs for safety. When writing on safety needs, Maslow asserts that “all that has been said of the physiological needs is equally true, although in lesser degree, of these desires” (p. 376). Just as an individual can become dominated by their physical hunger, so too can they become dominated by their hunger for safety.

How Math Anxiety Can Develop

The American Psychological Association defines safety as “a desire for freedom from illness or danger and for a secure, familiar, and predictable environment” (APA, 2018)11. Under this understanding, threats to safety would include anything that leads to: physical or mental illness, feelings of being or actively being endangered, and/or living in an insecure, unfamiliar, and unpredictable environment. These threats to safety can be caused by a plethora of influences, namely those from adverse experiences like poverty, war, violence in the home or the community, sudden disasters, shame, and abuse.

When safety is threatened and the need left unsatisfied, an individual is primed to live in an ongoing survival state. When circumstances prevent an individual from meeting their needs, these circumstances become a threat to that individual’s quality of life. These threats are registered as stressors and will naturally induce stress responses. Circumstances that threaten safety generally have a long onset and require multi-faceted, long-term solutions. Because of this the stress often persists. As the stress persists, so too does the stress response. Because their need for safety is unmet, more and more of an individual’s capacities and resources become devoted to satisfying that need. These conditions keep the individual in a disorganized state wherein their physical and psychological well-being becomes increasingly insecure.

Living in these conditions is inherently stressful as these conditions jeopardize safety and overtime interfere with the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis. Homeostasis can be understood as “any self-regulating process by which biological systems tend to maintain stability” (Britannica, 2024)12. In this way, the human desire to satisfy the needs expressed in Maslow’s hierarchy is the self’s attempt to maintain homeostasis on the physical and psychological levels. In their article titled “Physiology, Stress Reaction”, Brianna Chu and her team discuss the body’s response to stress13. They begin by stating that “any physical or psychological stimuli that disrupt homeostasis [results] in a stress response” (Chu et. al, 2022, p. 1). The article terms these stimuli “stressors”, and goes on to note that these stressors result in physiological and behavioral changes known as stress responses (p.1). When exposure to stressors is severe, frequent, or sustained, “the stress response becomes maladaptive and detrimental to physiology” (p. 1). Chu and her team note that stressful situations can trigger a “cascade of stress hormones that produce physiological changes” (p.1), namely the “fight or flight” response. The fight or flight response is beneficial when it is a reaction to an acute stressor. Heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing increase as hormones are released to help the individual handle whatever is causing them stress. Unfortunately, long-term or chronic stress leaves an individual dealing with an influx of hormones and physical changes that when sustained, lead to harm. According to the American Psychiatric Association, constant stress can result in: constant muscle tension (leading to conditions like tension migraines and chronic pain), exacerbated pre-existing respiratory issues, increased risk for inflammation, heart attacks, and strokes, mental health conditions like depression, and the gradual wear-and-tear on the body and its ability to compartmentalize and maintain homeostasis (APA, 2023)14.

In their work, Christina Young and her team noted that math anxiety can be associated with “decreases in working memory and attention . . . deactivations in brain areas needed for processing information . . . [and] increased activation in the amygdala (a part of the brain that regulates stress, fear, and other negative emotions)” (Young, et.al, 2012, p. 496-98)15. These effects make math anxiety innately disruptive to both learning and homeostasis.

This sustained disruption in turn feeds into the ongoing stress response, thus exacerbating the response and its negative effects on the individual. These stressors create an ongoing survival state wherein the individual is constantly reacting to threats to their safety. Whether these threats are present or associative, they are registered by the body as stress and responded to accordingly. Unfortunately, stress responses can become conditioned responses when stress is endured over time. This video from Course Hero briefly explains the concept of classical conditioning.

At its core, classical conditioning describes how behaviors can be formed around associations between events that become linked in an individual’s mind. Stimuli that trigger an involuntary response become paired with a neutral, or unrelated, stimulus. When this pairing occurs, the neutral stimulus becomes a trigger for the involuntary response. If your first time eating clam chowder ends with you hovering over a toilet bowl, you may begin to have negative feelings towards anything related to or reminiscent of clam chowder. These neutral stimuli could be the smell of clams, the sight of heavy cream, any food with a reminiscent mouth feel, or anything that the mind pairs with that event of food poisoning. The more intense and negatively impactful the event, the more likely an individual is to form negative associations, experience anxiety around that event, and begin to operate under anxious conditioning. Getting raged at for doing poorly, being forced to answer questions you don’t understand in front of your peers, struggling to complete assignments that require knowledge you never received – these are all common classroom experiences that aggravate the accumulation of stress and anxiety. In these scenarios an individual is left in overwhelming situations, unsupported. In order to feel safe, their capacities become increasingly dominated by recognizing and managing their stress and anxious associations with math. These associations are multi-faceted and can be paired with any life event or stimuli.

What Maladaptive Coping Can Look Like in The Classroom

Over time, living in this state of chronic stress can become traumatic as an individual becomes routinely overwhelmed by triggers and stress responses. Staff at Psychology Today write that:

“Psychological trauma is a person’s experience of emotional distress resulting from an event that overwhelms the capacity to emotionally digest it. The precipitating event may be a one-time occurrence or a series of occurrences perceived as seriously harmful or life-threatening to oneself or loved ones. People process experiences differently, and not everyone has the same reaction to any event; what one person experiences as trauma may not cause distress for another. Traumatic experiences undermine a person's sense of safety in the world and create a sense that catastrophe could strike at any time.” (Psychology Today, 2024)16.

Trauma can be acute or chronic, and what the mind and body interpret as distressing varies by the individual. Still, traumatic experiences are characterized by the lasting, negative impact they have on an individual’s ability to process stimuli and engage with their world. In his seminal work on trauma, The Body Keeps the Score, Dr. Bessel van der Klork writes that “the threat-perception system of the brain [is] changed, and people’s physical reactions [become] dictated by the imprint of the past” (p. 110)17. This means that even without the overt presence of the stressor, the body can be conditioned into a constant stress response. While anxiety is distinct from trauma, the effects of anxiety can still be traumatic because they prevent a person from feeling safe in their environment.

In terms of the classroom, safety might be best understood as “the perception that a learning environment is safe for interpersonal risk taking, exposing vulnerability, and contributing perspectives without fear of negative consequences” (McClintock, et. al., 2021)18. Under this understanding, threats to safety would include anything that makes a learner feel that sharing things about themself, their abilities, or their perspective would result in negative treatment.

How Math Anxiety Can Affect Learning Outcomes

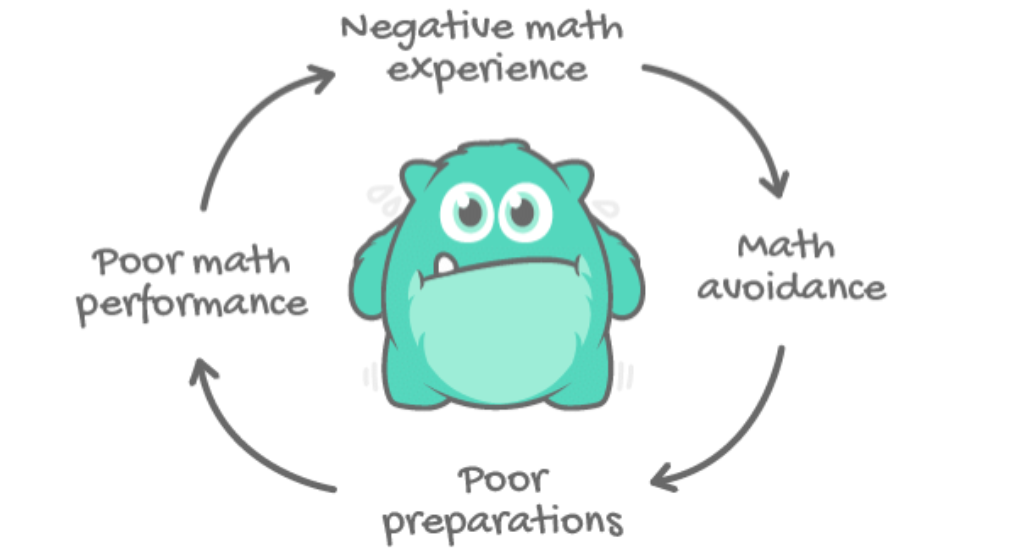

Because math anxiety can jeopardize needs and lock the body into stress responses, an individual becomes primed towards safety behaviors that are ultimately maladaptive coping strategies.

When an individual is prevented from meeting their needs, they begin to find ways to escape from their circumstances. These escapes are ways to cope with unforgiving realities. These coping strategies are maladaptive because they do not address the circumstances that lead to coping; rather, these strategies numb the effects of stress while robbing the individual of their capacity to improve their circumstances through self-advocacy and stress management. When it comes to anxiety, some of the most common maladaptive coping strategies are procrastination, maladaptive daydreaming, social withdrawal, negative self-talk, dissociation, binge behaviors, and substance abuse.

In the classroom maladaptive coping strategies might be missed or incorrectly interpreted by the instructor as malicious or intended to offend. Students who rarely turn in assignments, who are often late or absent from class, or who become disruptive or combative over mistakes/participation, may be dealing with math anxiety and the unpleasant realities that come with feeling insecure and overwhelmed. These strategies disrupt learning because they fix the student to their internal stress, preventing them from focusing on their lessons. These strategies are disruptive because they reinforce the stress responses and negative associations a student has with math.

Remember, math anxiety begins as a largely unconscious neurobiological stress response that keeps an individual at extremely high alert. No one chooses to have math anxiety, and while each individual chooses how they respond to it, math anxiety hinders the very processes that make effectively addressing the anxiety possible. In this way our students are caught in an awful catch-22 where experience has taught them that they are the problem and that true help may never come. This is why we as educators must take pains to be aware of the various realities our student populations face, and utilize the practices that will help our students succeed.

Practices That Exacerbate Math Anxiety

At this point, it is also important to note how certain practices can exacerbate math anxiety.

Any practices that are similar to a student’s past, negative math experiences can exacerbate math anxiety, specifically practices that impose authority, create negative public exposure, and/or that don’t account for gaps in a student’s knowledge.

Imposing authority involves coercing someone into submitting to your will. For example, when a student is chronically absent, demanding a rationale would be an intimidating and aggressive imposition. Creating negative public exposure involves drawing negative attention to a student. For example, cold calling struggling students to work out a problem or explain their reasoning induces shame and the fear of being rejected. Failing to account for gaps in a student’s knowledge largely involves not remediating required knowledge for things students are currently struggling with. For example, if students are struggling with finding the greatest common factor, they may need help strengthening their understanding of multiplication tables. Continuing to focus on the skills they do not have further emphasizes the disparity between the student’s desired ability and their actual ability without the promise of help. These practices (and others like them) create a hostile classroom atmosphere. They leave students feeling unsupported, stressed out, and more likely to cope maladaptively because these practices reinforce a student’s underlying negative associations towards math.

What We as Educators Can Do to Account for Math Anxiety

Because math anxiety is one in a subset of anxiety disorders, practices that alleviate the stress of anxiety can also be effective in alleviating math anxiety.

In situations where math anxiety is perceived, it is always better to privately voice observations and respectfully ask the student for clarity. Observations are different from assumptions, and this difference lies in heart posture and communication. When educators operate from a place of curiosity and compassion they are more likely to listen to their students without judgment, being sympathetic to their struggles. Often individuals who struggle with math anxiety feel like they are uniquely defective and alone in their struggle, so there are even times when appropriate self-disclosure is helpful. Sometimes, sharing relevant details about one’s own struggles with similar things can help students feel seen and supported by someone who can understand what they’re going through. What we share should be relevant, to the point, and encouraging. This appropriate self-disclosure can help strengthen rapport and create a non-threatening classroom environment.

Other practices that can alleviate math anxiety include, but are not limited to, validating student feelings (which involves expressing sympathy as opposed to solutions), normalizing mistakes and asking for help (which can be done through teacher modeling), teaching mindfulness practices like deep breathing or body scans, paired work with students strong in math, having clear expectations and routines, and consistent scaffolding. These practices are effective because they work against the root causes of anxious conditioning by providing positive associations with math and learning.

Math Anxiety Scenarios

What follows are four scenarios designed to explore math anxiety from the learner and teacher perspective.

The goal of this exercise is to practice recognizing symptoms of math anxiety, exploring the student experience, and discerning appropriate teacher responses. You’re free to reflect and discuss individually, with a shoulder partner, or in small groups. First, I’m going to present a scenario dealing with symptoms of math anxiety. Next, I’ll give you timed periods to think through the questions. After this, I’ll ask for volunteers to share their thoughts. As we discuss, feel free to engage with other people’s thoughts as well as your own.

- Mrs. Smith loves using exit tickets as formative assessment. She often gives students two problems to finish in the last five minutes of class. While Miriam always stays until the end of class, she has yet to submit a single exit ticket. What maladaptive coping strategy might Miriam be using? How might that strategy help Miriam feel “safe”? What about this situation might make her feel unsafe? What are some appropriate ways to broach the subject with Miriam? What makes them appropriate? What are some inappropriate ways to broach the subject with Miriam? What makes them inappropriate?

- Mr. Jones frequently cold calls students when reviewing concepts. John always leaves for the bathroom at the start of the review period and returns much later. Sometimes John returns to class high. What maladaptive coping strategy might John be using? Why might John be leaving? Why might John be returning to class intoxicated? What about this scenario may be stressful for John and why might it be stressful? What would be an appropriate course of action and why? What would be an inappropriate course of action and why?

- Mrs. Mack has noticed a change in Warren’s behavior. One day Mrs. Mack notices him mumbling to himself as he struggles to work through a problem. When she asks Warren what’s wrong, he replies that he’s “never been good at math” and that he “just needs to suck it up and figure it out”. Mrs. Mack leaves Warren to his thoughts, afraid to make him feel worse by asking more questions. Warren almost rushes from the room once class ends. What maladaptive coping strategy might Warren be using? Why might Warren have felt agitated? How can Mrs. Mack share her observations with Warren appropriately? What would make it appropriate? What things should Mrs. Mack consider before approaching Warren?

- Mr. Cruz regularly uses breakout rooms for group practice in his online class. Usually, things go well, but recently students have been complaining about the lack of mutual participation. Students say that Sarah joins the group but refuses to say anything or work on the assignment. Mr. Cruz had already noticed that Sarah attends class and turns in her work regularly. Now he realizes that Sarah works well individually, but not when she’s assigned to a group. What maladaptive coping strategy might Sarah be using? How might that strategy help Sarah feel “safe”? What about this situation might make her feel unsafe? How can Mr. Cruz appropriately acknowledge and account for Sarah’s aversion to group work? How can Mr. Cruz approach group work now that he knows about the lack of participation? What could be the benefits and drawbacks of that new approach?

Conclusion

Every day, students struggling with math anxiety go to class knowing that it could be one of the most grueling, humiliating experiences of their lives. The negative experiences they have with math amalgamate into pervasive associations that keep their needs unsatisfied and leave the student feeling unsafe. These associations lock the body and mind into a near constant state of stress and survival. Under these conditions, students are prevented from learning as their capacities become devoted to coping with these emotional realities. Unfortunately, these conditions incentive maladaptive coping which keeps students locked into a perpetual cycle of anxiety and poor outcomes.

By being compassionate and intentional, educators can account for math anxiety through more conscientious practices. Practices like validating student feelings, normalizing mistakes and asking for help, mindfulness, paired work with students strong in math, having clear expectations, and scaffolding can all help alleviate math anxiety. That is because, at their core, these practices help lessen the burden of stress by creating more positive associations with math and learning. When we approach math anxiety as an emotional response to overwhelming stress, we are more likely to help our students feel seen and understood. In this way we can begin to build stronger partnerships with our students and help them build the skills they need to overcome their obstacles.

Sources Cited

- Mathematics Anxiety—Where Are We and Where Shall We Go?

- Anxiety Disorders

- Mental Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders - Facts & Statistics

- A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications

- Needs Definition

- High Quality of Life Definition

- Maslow's "A Theory of Human Motivation"

- Safety Needs

- Homeostasis Definition

- Physiology, Stress Reaction

- Stress Effects on the Body

- The Neurodevelopmental Basis of Math Anxiety

- Psychological Trauma Definition

- Creating Psychological Safety in the Learning Environment: Straightforward Answers to a Longstanding Challenge

- The Body Keeps the Score

- Creating Psychological Safety in the Learning Environment: Straightforward Answers to a Longstanding Challenge

Resources

- Dealing with Math Anxiety - Mission College Santa Clara: This site covers signs and symptoms of math anxiety as well as how to encourage healthy math identities.

- Follow These Steps to Ease Student Anxiety in Your Classroom - Western Governor's University: This site offers various strategies for mitigating student anxiety.

- Helping Ease Student Anxiety - Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: This site offers tips on accounting for math anxiety and helping students build the skills that help them manage their anxiety.

- How to help kids manage math anxiety - American Psychological Association : This site covers causes and consequences of math anxiety and ways to manage math anxiety. Though it’s geared towards helping kids, these understandings can help adults too.

- How to Overcome Math Anxiety - Anoka-Ramsey Community College : This site offers signs and symptoms of math anxiety, a self test to see if you have math anxiety, myths about math anxiety, ten ways to reduce math anxiety, tips to study and prepare for doing math, and a list of helpful websites at the end.

- Reducing Math Anxiety - Ferris State University: This site gives ten ways to reduce math anxiety.

© Copyright 2024 Keyona Shabazz

Member discussion